Anthony Bartok

Remote Access

ESSAY | GALERIE POMPOM | NOVEMBER 2020

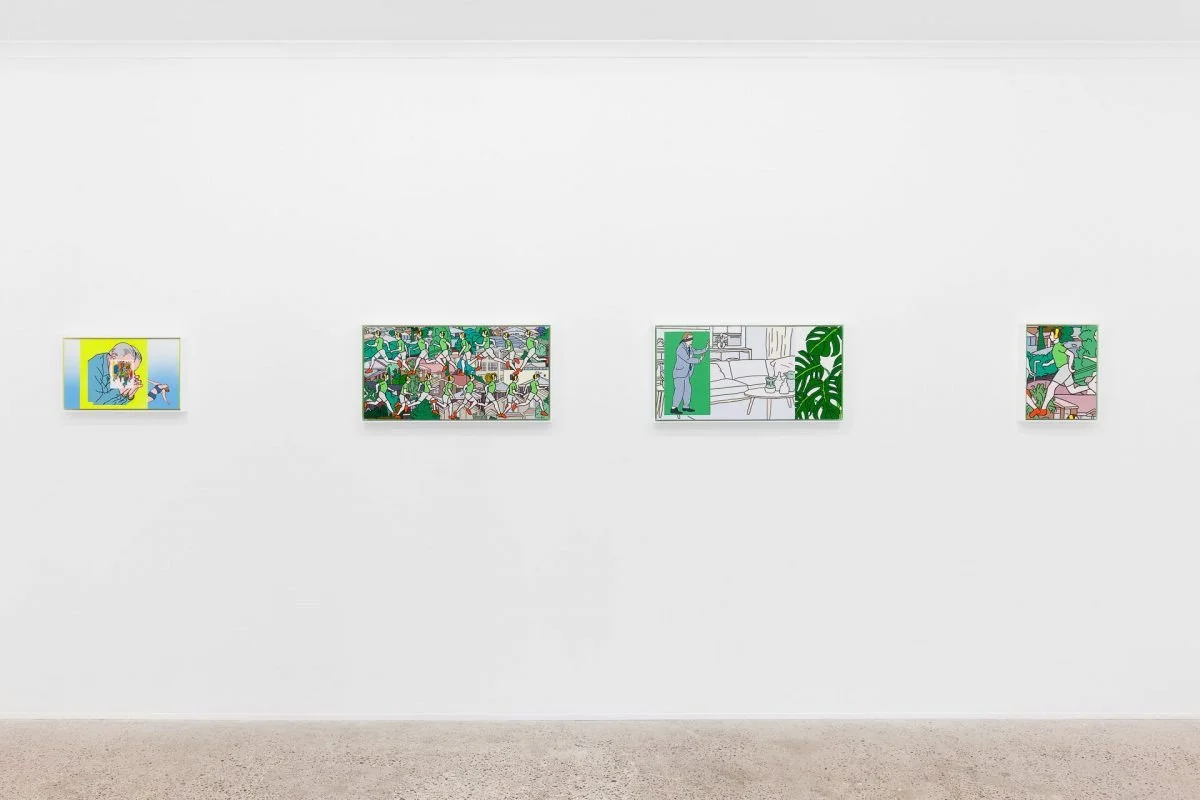

Working within an oxymoronic scaffold of profound banality, Anthony Bartok engineers everyday contradictions to critically jab our current moment. In his new series of paintings and screen prints, incongruous couplings expose cross-pollinations of industry and individual at a time when notions of privacy have been turned inside out; when the melding of work life and home life is catapulting us into an age of remote access.

‘Remote Access’ extends Bartok’s subversive, rolling exposition of twenty-first century existence, where individual foibles unfurl against a global backdrop. In his hybridised scenes, selfish ambition waltzes with contemporary capitalism; religion with industrial globalisation, personal intimacies with pervasive technology. Hands pursed and head bowed, the businessman in Pray prays to capitalism in the metonymic form of a frenzied department store sale. His supplications are heard only by a stripper dancing on the perimeter, her pathos pulling into an orbit of loneliness; and futility.

After mining imagery from Google, Bartok hand traces, scans and digitally collages his compositions, sewing together mundane moments that become densely loaded. Baudrillard’s increasingly relevant notion of the hyperreal is at play here, as Bartok both draws from and creates a virtual image regime ripe with semiotic potential. For Baudrillard back in 1981, simulation is not a replica of reality but a hyperreality in its own right, composed of endlessly exchangeable signs of reality without any causal connection to a knowable real. In an era of remote access, the real and the virtual mingle indistinguishably and the hyperreal reigns strong.

In Sky Mine, the non-objective intrusion of a gradient sky amidst a pallid aerial landscape poetically utters the anthropogenic cavity we are carving, literally, into the planet. The diametric perspectives – peering up to the sky and down on the landscape – signal the dizzying force at which humanity cannot see what is right in front of us. We look to the past for guidance and to the future for salvation, while presently the earth falls to pieces.

This sense of blindness, paralysis, is literalised by the blindfolded businessman in the painting House Plant. A vile trope of white Western power, the ubiquitous suited man stumbles forward encased in a claustrophobic grass green rectangle; blissfully ignorant of his surroundings. Bartok harvested the figure from a trust exercise picture – an ironic origin given this man is emblematically untrustworthy. The quintessential IKEA apartment and indoor fern fuses the timeless idea of home with the 2020 symptom of working from home; a habitual bubble that has perhaps rendered us, too, blind to the vicissitudes of the ‘real’ world.

Couple Office extends these mutated dynamics of ‘home’, where a couple in bed stare hollowly into a laptop. Surrounding this vignette is a Keith Haring-esque grid of offices, the nauseating neon green and black palette demolishing any distinction between the figures and their computers. That the couple themselves are presented in a screen shape doubly exposes our fraught culture of screens – Baudrillard’s hyperreality incarnate. Many of Bartok’s viewer’s will indeed view this series through the glow of their screens (amidst Covid limitations), fixing us firmly and uncomfortably in the couple’s lukewarm bed.

Bartok’s flat colours and minimalist linework possess the infantile aesthetic a children’s book or cartoon, forming a kind of existential guidebook to contemporary life. Yet his works are not a pulpit for ‘changing the world’ or overt social commentary; rather they resound, in Bartok’s words, a ‘detached ruminating’ and ‘a bit of cheeky venting’. With a tragicomic tenor, he divulges our own complicity in the paradoxical absurdities of today.